The July Effect: Two summers. One Unsolved Mystery

The weeds grew, and the wind blew, and facts shifted away to legend.

I. What’s in the Box??

It was July 2022, and I was trying too hard.

I’d spent eight hours that Sunday reading old newspaper clippings and half-remembered notes, trying to figure out how to make a story into a story. The sky outside had gone that particular watercolor pink it gets in mid-summer, when the air conditioners hum like insects and the insects hum like machines.

I was in “masculine mode,” as I called it—gathering, organizing, overloading. At some point I remember saying aloud, “I just need to get everything on the website,” as if that would contain it. As if a digital structure could hold this much silence.

I’d been neck-deep in Bluff Point research for months—combing old newspapers, scanning dusty microfilm at the Penn Yan library, tracing rumors of vanished walls and ancient stones.

One night in July 2022, I emailed the Yates County History Center to ask if there had been anything new since David Robinson’s 1998 article in The Crooked Lake Review. He’d ended that piece with a call for local volunteers to excavate the ruins—an effort that, as far as I could tell, had never materialized.

The reply came the next day: yes, they had a file on the ruins. But more interestingly, they’d just received a box. A recent donation—unprocessed, possibly full of materials related to the Bluff Point ruins.

My heart raced. A box? Just sitting there, waiting? It felt fated.

I drove to the archives at the Yates County History Center—an hour’s drive—within the week.

(Excited selfie on the way to find out “what’s in the box?”)

The staff brought out the box and set it on the table in front of me. It had been donated by a man named David B. Kelly, an academic who’d researched the ruins for more than forty years before deciding to let it all go. It was, in a way, his farewell to the mystery.

I opened the box like I was cracking a tomb. I wanted revelations.

But as I leafed through each envelope, report, and scribbled annotation, a chill sank in: I had already seen all of it. Every clipping. Every report. Every theory. I’d tracked them down myself, one by one.

There was no there there.

II. Old Legends Never Die

Later, back in my apartment, I tried to take it all in.

That was the thing about the Bluff Point Ruins: constant hope, constant disappointment.

I had been building a website, transcribing articles to audio. Cataloguing findings. It sat there, endlessly unfinished and would continue to sit there for nearly three years until I realized that what people needed were articles on a traveled road: a Substack. Not a website. I was stuck in the 90s.

But in the meantime, I was still trying too hard. My mind was both tired and ablaze. Fireflies blinked outside the window like unread messages from another time. I could hear an air conditioner above me. Another below.

I found yet another article in the old New York State Historic Newspapers.

“If legends did not exist, man would invent them,” the article began, quoting Voltaire. “One of the most interesting of local legends is substantiated in stone and though now buried beneath the soil, refuses to die.”

Printed in the Penn Yan Chronicle-Express on July 2, 1964—58 years before—nearly 90 degrees that week, according to the almanac—the piece read like a dispatch from another realm. Perfect for a dreamy July night. It told the story of the Bluff Point ruins again, this time through the voice of Berlin Hart Wright, son of the man who had surveyed them back in 1880.

The article was a tangle of folklore and fact, full of phrases that made my skin prickle:

“the mound dwellers rise again”…

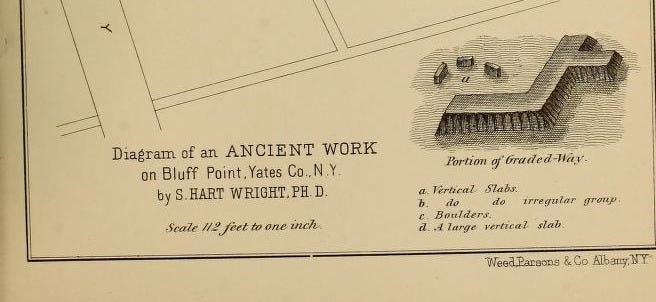

Samuel Hart Wright and his son Berlin Hart Wright, in 1880, had mapped the site—14 acres in total—where walls and “graded ways” once ran in mathematically precise lines. He described rooms whose dimensions matched the depth of the soil, intersections where posts once held roofs, and slabs arranged in arcs, circles, and squares—like a rural Stonehenge. At the northwest corner of the site, a solitary standing stone rose eight feet high, “a lone sentinel guarding the community.”

There was even a discovery of charred maize in a hidden cache beneath the sandstone.

Ashes. Burned corn. A vanished structure.

Proof, or something like it.

Vanished, like everything else.

I already knew all these details by heart.

I knew the stones, taken by a man named Howard Hemphill in the 1800s, were hauled away to help build the Wagener mansion. The ruins themselves disassembled and reassembled into something else. Something denuded of their magic.

Yes, I knew all this already. But there was something new, something alive in the title “Old Legends Never Die, They Just Fade to Bluff.”

“Stony hearted scientists were inclined to regard the rock formation, strange, extensive, and "planned" as it seemed to be, as a natural phenomenon. Except for some stones in a hedge row, the evidence was covered over by a subsequent tillage of the fields, the weeds grew, and the wind blew, and facts shifted away to legend.”

I imagine Hemphill working hard during those summers, dust thick, the sun hammering the back of his neck as he pried the huge stones apart. He had done his due diligence as he saw it, talked to some of the remaining Seneca still in the area. They did not claim the site as theirs. So he figured, as many had after him, that it was just natural, or at very least no longer important.

I imagine he told himself it was practical—using those stones to build something real, something literally foundational. Something that kept houses warm in the winter and cool in the summer. But I also wonder if he felt it. The trace of something precious vanishing into thin air.

But never really leaving.

The Abraham Wagener house on Bluff Point overlooking Keuka Lake.

III. The July Effect

So, now here I am in July 2025, and it’s all still there, curling at the edges of campfire smoke: the mystery.

There’s just something about July.

More than half of the articles published about the Bluff Point Ruins have been in July.

Why?

And what was that summer of 1964 like when The Chronicle Express put out its Special Summer Issue with its alluring pull quote:

“It’s love at first site—for little Yates, land of legend and romance, of vineyards and visionaries, or waterways and the wildwood.”

The big summer issue was full of magic. Playhouse and theater coming attractions. Wine, parks, museums, and of course enticing local history like “Old Legends Never Die.”

That summer, two million people visited the Finger Lakes, already a burgeoning wine and vacation region that was somehow vast and yet quaint.

In 1964 you could still walk from Birkett Mills to the Chronicle-Express and get a buckwheat pancake recipe, a ghost story, and a bundle of mimeographed meeting minutes from the Historical Society—all within an hour. The boat company was cranking out fiberglass cruisers for a new generation of lake explorers. Teenagers lounged under marquee shadows and Mennonite farmers rode by with cartloads of corn.

The Chronicle‑Express, founded in 1834, still printed weekly issues from the same building that July—its lawn dwarfed by parked cars and perhaps a Penn Yan Boat Company truck, which by the early 1960s was turning out fiberglass vessels to tourists prowling the Finger Lakes—a contrast of old stone and new plastic.

I imagined July 1964 was hot and slow, the village’s old stone and brick façades baking in the sun. The historic district—Main, Court, Liberty, and Elm—stretched before me like a movie set, each building steeped in stories: the Greek Revival courthouse, the First Baptist, and just down Elm, the old Sampson Theatre, once a vaudeville stage, then a mini‑golf course, now a quiet relic of the past.

By late evening, the Community Chorus would rise in the courthouse park—a midsummer concert, their voices drifting over the Civil War monument. Somewhere nearby, teenagers from Penn Yan Academy—class of ’64—were lying on the hoods of Chevys, watching stars blink above Keuka Lake, daring each other to jump from the docks, peering into the dark, telling ghost stories.

After all, it’s people who carry the stories—the living stories that live beyond the edges of the page.

IV. Giving Up the Ghost

So, as I thought about the disappointing box what I realized was the real treasure was the man who had put it together.

David B. Kelly.

He agreed to meet with me.

On another hot July afternoon in the stuffy Yates County Historical Society back rooms—after I requested a fan—Kelly told me about lost artifacts, family collections, stone tools, a metal arrowhead that vanished into someone’s personal stash.

Keuka College, he said, once held ceramic vessels discovered near the site—but they’d been sold off without proper provenance. The Ogden Collection had gone missing. The artifacts, he said, were “just gone.”

And yet, he still had hope for one thing: LiDAR.

“Get someone to do LiDAR,” he told me. “You don’t even have to dig. Just fly a plane over it. If anything’s left, it’ll show up.”

LiDAR—short for Light Detection and Ranging—uses laser pulses fired from aircraft to map the ground in exquisite detail, even through thick vegetation. It’s how researchers have found ancient cities in the jungles of Central America without disturbing a single stone.

His voice was tired, but his eyes sparkled when he said it. I walked out of the meeting with a new kind of thread:

Hope for the future.

I still have no idea how to fund a LiDAR survey for Bluff Point.

But I do know this: if I can tell the story well enough, maybe someone else will carry it forward. Maybe that’s my part in it. Not the excavator, but the torchbearer.

The ruins are still there, waiting. The mystery, still unsolved.

And if we ever stop asking about it—if we ever stop wondering—maybe that’s when it disappears for good.