Resurrecting Eve

A lost lesbian book, the weight of carrying someone else's story, and the sacred work of recovery

This is not just the story of the recovery of a lost book, but the unresolvable ache that comes with carrying someone else’s voice across time, especially when you didn’t ask to. The guilt. The grace. The strange, sacred trust.

This piece is also published at The Cosmographia Codex, the newsletter for my small press.

Here at Legends of the Lost, I write about the stories that fall through the cracks—ruins, forgotten voices, ancestors whose lives were nearly paved over. But I’ve always had trouble writing about Eve Adams.

It’s not because her story is unknown. In fact, it’s finally getting some of the attention it deserves. Eve Adams—born Chava Zloczewer in Poland in 1891—was a Jewish immigrant, anarchist, writer, and bookseller who ran a tea room in 1920s Greenwich Village called Eve’s Hangout. The sign on the door famously read: “Men are admitted but not welcome.”

Pulled from Atlas Obscura. Eve Adams with her siblings in 1925. Courtesy of Eran Zahavy (Zlocower)

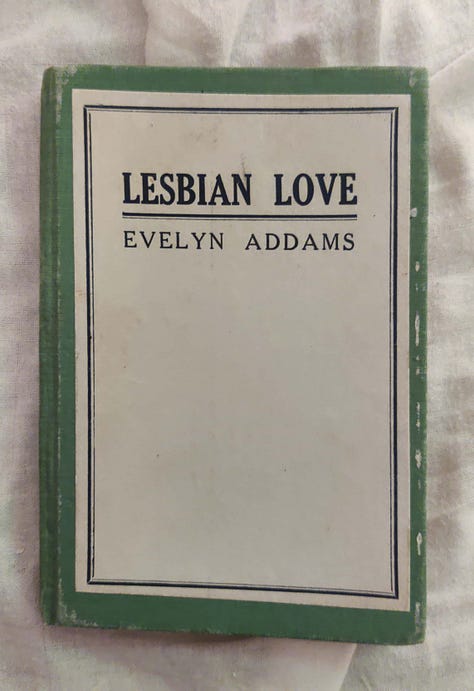

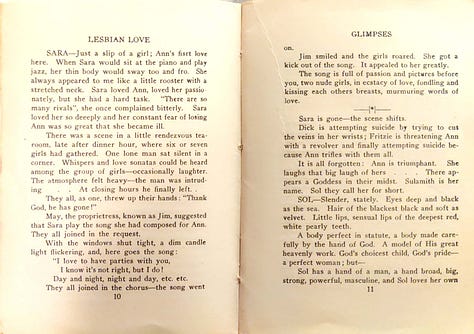

Eve was openly lesbian, openly political, and utterly unconcerned with making herself palatable. In 1925, she published a small, self-funded book called Lesbian Love, a fictionalized, possibly autobiographical series of vignettes about women who loved women. Tender, frank, and sometimes messy, it was unlike anything else at the time—not clinical, not tragic, not written for a male gaze. It simply, in soft and direct short stories, stories of women like her.

A year later, the FBI raided her tea room, seized her book, and charged her with “obscenity” and “disorderly conduct.” She was deported in 1927. In 1943, she died at Auschwitz.

For decades, Lesbian Love was believed lost. Destroyed. Erased like so many queer artifacts from that era.

And yet—I somehow ended up with the only known copy.

The Book That Found Me

I didn’t find Lesbian Love in an archive or rare bookshop. I found it on a mantle in the common area of a student apartment in Albany in the late ’90s, while I was still in college. People would leave books they didn’t want anymore—free for the taking. I thought it might be a novelty, maybe a handmade zine made to look like it was from the 1920s. It seemed too unlikely to be real.

But something about it felt precious, even before I knew why.

So I kept it. For fifteen years, I carried it with me from place to place. In Spring of 2013, when money was particularly tight, I started researching some of the old books I’d accumulated to see if any were worth anything. That’s when I realized what I had.

Lesbian Love wasn’t worth anything.

It was priceless.

Who Was Eve Adams?

I started reading everything I could about Eve. Her life reads like an epic of resistance and survival—except the survival part didn’t last. She’d arrived in the U.S. in 1912 and quickly aligned herself with anarchists, labor organizers, and writers. She sold leftist newspapers on the street. She published her own writing when no one else would.

And she dared to tell lesbian stories at a time when doing so could—and did—ruin a life.

Her book was considered obscene not because it was salacious, but because it was sincere. In the stories, women fall in love, suffer heartbreak, make mistakes, and try again. They are human.

The Editorial Process: Listening as Labor

When I finally sat down to read and prepare the book for reissue, I didn’t approach it like a traditional editor. I approached it like someone tending a sacred site. I scanned the original—uneven type, sometimes smudged ink.

I didn’t want to change it, obviously. I didn’t want to erase the very marks of Eve’s presence on the page. But I had to transcribe it to a Word doc to make it readable as an ebook. My copyedits were light, careful, reverent—just some formatting and punctuation here and there.

During those 11 years between discovering the significance of the book and publishing the reprint, I did a lot of handwringing, but I did make some good decisions. I shared scans with historian Jonathan Ned Katz, who included Eve’s story in his deeply researched biography.

I spoke about the book’s history to The New Yorker, the New York Times, and on podcasts like Cruising pod, a podcast about lesbian bars in America. One of its hosts, Sarah Gabrielli, will incorporate that interview into a book coming out by Beacon Press next June. The first chapter: Eve’s tearoom.

I published Lesbian Love as an ebook through my small press, Cosmographia Books, and made it available at an accessible price.

And finally, to my contact at the auction house Bonhams, who researched and wrote a beautiful history on Eve and the significance of her book, and then sold it for $14,000, $10,000 of it going to me, which kept me and my then-partner afloat during yet another dry spell common to people in the literary arts.

So, I received a great gift from Eve, 100 years after the book was written. And I still don’t fully understand why.

So after today’s post-interview for the forthcoming book on lesbian bars in America—a project I wholeheartedly support—I got off the call and felt hollow.

I still felt like I hadn’t done enough.

The Gift and the Weight

I’ve said this before: I didn’t feel like I deserved the book.

I’m not Jewish, like Eve. I’m not a lesbian. I’m not even an anarchist. I’m not the one who risked prison for publishing these stories. I’m not the one who was deported and murdered for daring to live authentically.

I’m a writer and publisher. A woman who’s dedicated her life to books, to words, to protecting stories that might otherwise disappear. I’ve spent years scraping by to keep that mission alive. There were times when money didn’t come and I made myself sick with worry. I could have taken a safer job—maybe my nervous system would’ve thanked me—but my soul wouldn’t have.

Maybe that’s where Eve and I meet.

We were both women who wanted to live authentically, to make art, to speak freely.

She was punished for it.

I was entrusted with the aftermath.

Is the Story Over?

I’ve thought about publishing a hardcover facsimile edition of Lesbian Love—one people can hold in their hands. Maybe with scans from the original on one side, and clean type on the facing page. Maybe including the original illustrations. Maybe with a brief introduction, pulling together all the good research that has already been done.

I’ve been in touch with people connected to her family. They’ve been kind. Supportive. Grateful that the book has been protected, that her story is being told.

A publishing student in France wants me to send her Eve’s book to translate into French. Once again, I am not sure what to do. Will she do a good enough job? Would it be wrong to say no? Wrong to say yes?

It seems with this journey, I’m always wondering if I’ve done enough. Or if I’ve done too much. If I’m acting out of love, or out of guilt. If I’m trying to earn something that was given freely—or if I was given it because I’d know how to carry it.

Is the story over?

Have I done my part?

Or is there more to do?

I don’t know.

This is the weight of carrying someone else's story, and the sacred work of recovery.

The Presence of Something Sacred

As I finished writing this, a scarab beetle flew onto my porch, landing a few feet away. This had never happened before. Scarab beetles symbolize the cycle of death and rebirth. I felt its presence as a good omen. I watched it crawl along the windowsill. I felt it asking me to be still, to feel its sacredness.

Sometimes we are honored with the presence of something sacred. When it comes, it is good to let ourselves feel it, not doubt or question whether we deserve it.

Maybe, in the larger scheme of things, resonance is more important than reciprocity.